A couple of Christmases ago, before the Swine Flu outbreak, I gave a foodie friend a book from Italy, Pigs and Pork. Coincidentally, I unwrapped the same book from my husband. He knows my love for the flesh and skin of pig – not the kind you pass and kick, the kind you slow roast to a snap and a pop of the crackling. The book’s slightly skewered translation says scratchings for what I take to mean cracklings. And the title — how does one separate the pig from the pork? After all, Pigs R Pork.

The book says there are approximately 960 million pigs in the world, roughly a third of them in China. Europe has 243 million and the United States only 95 million. Boiled Pig’s Cheek with Garbanza Beans is just one of the book’s recipes I have yet to make. But now that we’re getting succulent pork dishes in restaurants like Chifa and Lolita, I may not take the time.

In Chinese astrology, I’m a goat and my most compatible match is the pig. Alas, I am married to a rat. But he must have ascendant pig qualities: nice to a fault, they delight in eating good food and lovemaking, believe in the best qualities of humankind, are highly intelligent, and make wonderful life partners due to their hearts of gold and love of family.

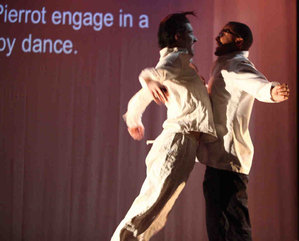

Not only is pork the other white meat, pig is featured in fairytales, cartoons, the Babe movies. Philly’s most celebrated theater company calls itself Pig Iron Theater. And New York’s redoubtable Mabou Mines, does an off-off Broadway production Ecco Porco. Actor Frederic Neumann starred as Gonzo Porco. About a pig by that name, the play runs four hours – enough to roast a suckling in time for an aftermath party.

After seeing the play in the East Village one brittle January night, we found Col Legno’s cozy room still open. We warmed up not far from the brick oven where they bake quail, pizza, and white beans with sage in glass flasks.

I have eaten wild boar throughout Eastern Europe where it is still available in butcher shops and featured on the menus of fine old hotel restaurants. Its musty taste surprised me and reminded me of the deep tones of the marrow sauces of my childhood. In honor of Gonzo, we ordered Col Legno’s Pasta with Wild Boar sauce – a Bolognese with finely chopped boar and sage.

Zimne Nogy (literally, cold feet) is pickled pig’s feet — Souse to y’all. You can go into a bar in Poland and order “binoculars and jellyfish” — two shots of vodka and a small plate of Zimne Nogy. Although I would not eat the stuff as a kid, I now ferret it out wherever I go. Krakus Market in Port Richmond prepares the best I’ve had locally. But I adore the Crispy Pig’s feet at Cochon. And I’m heading up to Northern Spy in the East Village soon as I can to try their shredded pig’s feet wrapped around mustard greens, breaded, then fried! northernspyfoodco.com.

On cold winter Sundays, my family’s favorite was a huge (and cheap) fresh ham, slow cooked until it fell apart. Pepper, salt, garlic, and maybe ginger or cloves, made up the limited palette of spices in the Polish “Kuchnia.” It was always good enough to eat like Guinea islanders, who, normally vegetarian, annually binge over a three-day feast on the pigs that ferret out their root veggies.

Once, after a visit to Taller Puertoriquenno up at 5th and Lehigh, we stopped into a Puerto Rican restaurant down the street. I looked over the unfamiliar menu, unsuccessful in my attempts to wrest meaning from our surly waiter, who, it later dawned on us, had feigned insufficiency in the Queen’s English.

Cuchifritos are crisply fried pork parts that include ears, tails, and stomach. I used to get them from K-Rico Bakery in Phoenix and they were mouthwatering. Since I’ll eat anything fried, when the word Cuchifritos popped out, I ordered it.

The waiter crooked his eyebrow, smirked, and bowed as he wheeled away to the kitchen. Shortly, he placed before me a plate of what looked like lukewarm, undoctored, off-brand baked beans with wilted, pasty-looking triangles poking through here and there. He stood at attention, waiting for me to dig in. The first rubbery bite was undistinguishable from an old girdle.

“Do you know what you are eating, Senora?” I smiled weakly, trying to chew as he hastened to tell me. “Pig’s ears.”

I offered a taste to Herb, a non-practicing Jew, who, nevertheless, does not eat pork. He declined.

“Oh, well, would you mind bringing me the chicken like his and wrapping this up to go? My husband will love it,” I said with a wink at Herb.

Herb told me a story about a man in Israel who needed a new heart valve, and how the rabbis, after much Talmudic discussion, decided to approve the use of a pig’s valve. Since pigs, like us, are omnivorous and have similar tissue makeup, we use them in medical research. I asked if he’d heard about the researchers’ latest fear, that, like the transfer of the HIV virus from animal to human, something similar could happen with pigs.

“Well,” Herb began after asking the waiter to pack the remains his chicken, “that came from eating monkey. So, if the same hasn’t yet happened from eating pig all these millennia, maybe it’s OK – even though I still wouldn’t.”

At home I placed my foam carton on the counter and turned to read the mail. My husband rummaged behind me. “What did you bring me?”

“Oh, just some leftovers.”

“Well, this is really fall-apart delicious. Best I’ve had.”

I spun around. The pig’s ears had turned into something other than a silk purse. As I watched my husband tucking into Herb’s chicken, I pictured Herb opening his carton tomorrow. Oink vey!