Who needs borders, anyway?

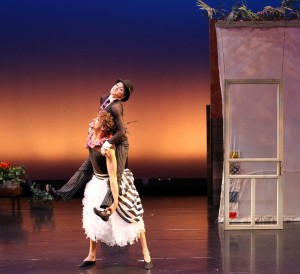

Phillips: Nervous energy above all.

By MERILYN JACKSON

Several years ago, I painted my office a color called Spalding Gray. Yes, Sherwin Williams actually has such a color– SW 6074— and when I saw it I thought, what better way to make a small commemoration to the monologist/raconteur who had died earlier that year.

I had first seen Spalding in the 1980s in Swimming to Cambodia, his narrative one-man show at the Painted Bride about the making of the film The Killing Fields. Like everyone who ever saw Spalding, I was taken by the vividness of his storytelling and saddened that he most likely died by jumping off the Staten Island Ferry after a long and painful struggle to recover from a car accident.

Thaddeus Phillips— international theater creator, actor, writer and one-man verbal cyclone— follows in Gray’s wake, though I trust that will remain a metaphor. After receiving his B.A. from Colorado College, Phillips studied scene design and puppetry in Eastern Europe, where he may have acquired some of his pitch-perfect accents. He is artistic director of The Lucidity Suitcase Intercontinental, whose original theater is often based on Phillips’s actual travels and laced with references to current events. He premiered his latest work in a string of idiosyncratic successes— 17 Border Crossings— at the Painted Bride earlier this month.

The new South Philly

When he’s in Philadelphia, Phillips happens to live around the corner from me in South Philly with his wife and collaborator, the Colombian-born Tatiana Mallarino. The area south of Washington Avenue has become peopled with the city’s dancers, actors and performing artists who frequently collaborate or otherwise interact with each other, if only by attending each other’s performances for moral support.

Phillips transcends the kind of one-man sit-talking, water-sipping show that Spalding Gray created. He ramps his performances up with physical movement (he’s a pretty good tap dancer, when he’s of a mind), acting, a plethora of authentic-sounding accents in any language he affects, and ingenious stagecraft that includes lighting, the latest high-tech gadgetry and the oldest low-tech slight-of-hand.

As the audience settled in, Phillips worked the crowd like a maitre d’ in a fine restaurant, greeting people, hugging some, guiding some to better seats. Was it all part of the show or just his way of sloughing off some nervous energy before getting down to business? But nervous energy is what seems to drive Phillips.

Less frenetic

He must have been considered a skeptical and irrepressible student. Yet he is not so neurotic as Gray was, and in Border Crossings he slows himself down to a deliberate, less frenetic pace than in earlier works like Lost Soles, Flamingo/Winnebago or ¡El Conquistador!, all of which were hits at recent Live Arts/ Fringe Festivals.

Shakespeare is a frequent source for Phillips. To set the tone for Border Crossings, he recites the lines from Henry V’s St. Crispin’s Day speech, which mentions what was the first passport: a letter of passage signed by the king. Traveling in the last decade has become a trial, but even more so with the itinerary Phillips took on. He really did travel (and study) in the Czech Republic, and then on to Slovenia, Israel, Jordon, Cuba and Colombia, not necessarily in that order.

His retelling of how he experienced the border guards and how the culture of baksheesh varies from country to country is authentic. It reveals how freedom and free access to common goods and money informs value.

Israel $50, Jordan $2

In Eastern Europe, for instance, a pack or a carton of cigarettes gets you through customs. At the Israeli border, a $50 bill gets you by, while a short while later in Jordan only $2 suffices, except that you might have to submit to multiple shakedowns by the same guards at different border stages.

For each of the 17 crossings, Phillips updates the old vaudeville card and easel mode of announcing a change of scene by flicking on an iPad to indicate the number of the next crossing. A simple bar of fluorescent lights across the stage, designed by Maria Shaplin and operated by Bob Adamski, performs multiple duties from a rickety train to, hilariously, a ski lift, but I won’t give away how.

In this work, Phillips becomes his most frenetic, drawing the Amazon across the stage with chalk to illustrate the confluence of Colombia, Brazil and Peru. In this curly little delta there are no border guards and you can cross from country to country freely.

Costly stupidity

With dizzying incisiveness, Phillips shows us the irony, costliness, stupidity and inconsistency of crossing borders. In the end Phillips is talking to Pablo in Juarez, where Pablo asserts we are all aliens and then manages, finally, to sneak across the border to the U.S. Phillips is already at work on a new piece, Whale Optics, which he’ll workshop at the Live Arts lab on Fifth Street on April 18 and 23. For more details, click here.

Spalding Gray may have had a paint named after him, but Phillips’s work is so heady and criss-crossed with twists and turns that they ought to at least name a screwdriver after him.♦

Originally published by Broad Street Review, 4/11/2011

http://www.broadstreetreview.com/index.php/main/article/thaddeus_phillipss_17_border_crossings_2nd_review